Graphs

Content Note

This is a second introduction to graphs that assumes you’ve at least seen them before. Take a look at the 61B version if you feel lost!

What’s a graph? #

Formally, a graph is a set of vertices with a set of edges connecting them. A graph can be defined as $G = (V, E)$ where $V = {A, B, \cdots V_n}$ and $E = {{A, B}, {B, C} \cdots }$

For an ordered graph where vertices are numbered, $E$could be represented as a set of ordered pairs instead: $E = {(A, B), (B, C) \cdots }$

(Insert image of graph)

Concepts and Definitions #

A neighbor of a vertex is another vertex that is next to the original vertex. Formally u is a neighbor of v if ${u, v} \in E$.

An edge is incident to the two vertices that it connects

The degree of a vertex is the number of other vertices neighboring. If the graph is directed, the degree can be split into the in-degree (number of incoming connections) and the out-degree (number of outgoing connections).

- The sum of vertex degrees is equal to $2 |E|$.

- Proof: Count the number of incidences. Each edge is incident to exactly two vertices, so the total number of edge-vertex incidences is $2|E|$(i.e. two times the number of edges).

- The degree can also be defined as the number of incidences corresponding to a particular vertex v. Therefore, the total incidences is the sum of all degrees for all vertices!

A path is a sequence of edges. These edges must be connected, i.e. a path could be $(v_1, v_2), (v_2, v_3), (v_3, v_4)$.

- If there are $k$vertices, then a path should have $k-1$edges!

A cycle is a special path that begins and ends on the same vertex.

- Unlike a noncyclic path, there should be the same number of vertices as edges in a cycle.

A walk is a sequence of edges that could possibly repeat a vertex or edge.

A tour is a walk that starts and ends on the same vertex. Additionally, it cannot have any repeated edges.

- An Eulerian walk is a walk that uses every edge exactly once.

- Doesn’t require all vertices to be connected! There could be an isolated vertex with 0 degree.

- An Eulerian tour is a tour that visits every edge in a graph exactly once**.**

- Theorem: any undirected graph has an Eulerian tour if and only if all vertices have even degree and is connected.

- Proof: You need to use two incident edges every time you visit a node (to enter and leave). So when you enter, you need another edge to be able to leave! If a vertex has an odd number of edges, then you get stuck on that vertex with nowhere to go once you visit it.

Here’s a handy summary, adapted from an explanation by Dustin Luong:

| end anywhere | start = end | |

|---|---|---|

| repeated vertices ok | walk | tour* |

| repeated vertices not ok | path | cycle* |

*Eulerian if it uses each edge exactly once.

Two vertices $u$and $v$are connected if there exists a path between them.

- If all vertices are connected, then the graph is considered a connected graph.

A complete graph is a graph where every vertex is connected to every other vertex by exactly one edge. Complete graphs have some nice properties:

- Every vertex is incident to $n-1$edges (if there are $n$total vertices).

- The sum of all degrees is $n(n-1)$.

A tree is kind of like the opposite of a complete graph in that it has the minimum number of edges in order to ensure all vertices are connected ($v-1$ total edges). Here are some properties of trees, from a graph perspective (If you aren’t already familiar with the recursive definition of trees, head over to the 61B guide first to brush up on it!)

- Trees are acyclic and connected.

- Leaves are vertices that have degree 1.

- In a tree in which each parent node has 2 children, the root is a single vertex that has degree 2 and non-leaf vertices have degree 3.

Hypercubes #

A hypercube is a specific class of graphs that have highly connected vertices. In order to understand them better, let’s start building some up:

Every hypercube has a dimension $n$. A 1-dimensional hypercube is simply a line (2 vertices connected by 1 edge). Not too exciting:

A 2-dimensional hypercube is a square (4 vertices connected by 4 edges). Still pretty familiar:

A 3-dimensional hypercube is a cube (8 vertices, 12 edges):

Now, let’s get to the interesting stuff. How do we construct a 4-dimensional hypercube?? Well, let’s figure out how we went from 2 to 3- we essentially duplicated the existing hypercube, then connected corresponding vertices (ones that are in the same relative position):

If we do this again for the 3-dimensional hypercube, we’ll get this 4-dimensional hypercube, which has 16 vertices and 32 edges:

You might have noticed a pattern in how many vertices and edges a hypercube has. Here are those properties stated more formally:

- A hypercube has $2^n$vertices.

- A hypercube has $n2^{n-1}$edges.

Hypercubes are super useful, particularly for representing bit strings. If we have an $n$-dimensional hypercube, then we have enough vertices to represent all possible permutations of 1’s and 0’s of length $n$. Every edge would then represent the act of flipping exactly one bit.

Planar Graphs #

A planar graph is a graph that can be drawn without having two edges overlap.

Euler’s Formula states that a connected planar graph has two more vertices and faces than the number of edges:

$ v + f = e + 2 $

Let’s take a look at some examples to convince ourselves of how this works:

(A triangle has 3 edges and two faces: the inner face and outer face.)

(This shape is connected, but there is no enclosed face so the only face is the outer face.)

Another consequence of Euler’s Formula is the inequality that holds for connected planar graphs:

$ 3f \le 2e $

This inequality states that any planar graph with 2 or more vertices must have at most 3 faces for every 2 edges. We know this because the smallest possible face is a triangle. If we plug this into Euler’s Formula, we can eliminate one variable to get $e \le 3v - 6$. This makes it much easier to figure out if a graph is planar or not, since faces are often difficult to count.

Proof of Euler’s Formula #

Let’s use induction!

Base Case: Let there be 0 edges and 1 vertex. This means there’s only 1 (outer) face as well. In this case, $v + f = 1 + 1 = 0 + 2$. This works!

Induction Step:

Let’s consider the case of a tree. Then, we know that there are always 1 fewer edges than vertices, and only one face:

$v + 1 = (v-1) + 2$ works!

What about something that’s not a tree? Well, things get a bit tricker here.

- Let’s consider a graph:

- Now, let’s start with the tree corresponding to the same number of vertices as the original:

- Now, we’ll keep adding edges to enclose faces until we reach the number of edges in the original:

- We’ll notice here that for every edge we add, a new face is created!

- Therefore, we can plug this fact into our inductive hypothesis (that Euler’s formula works) to get $v + (f+1) = (e+1) + 2$.

Nonplanar Graphs #

Although nonplanar graphs don’t share many of the nice properties planar graphs do, they’re often more accurate representations of real life. They can also be used frequently in proofs to prove that a graph must either be planar or non-planar.

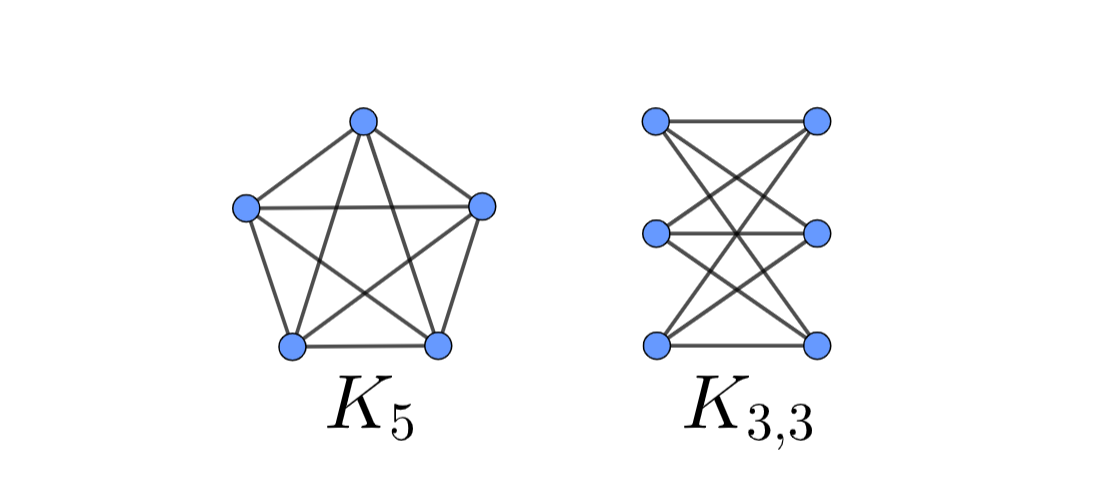

There are two famous non-planar graphs that are worth taking a look into:

K3,3 #

$K_{3,3}$is also known as the “utility graph” because of its connection to a popular puzzle: given 3 houses and 3 utilities (water, gas, electric), how can we draw a line connecting each house to every utility without having any of the lines cross?

I’ll save you an amount of suffering by spoiling the answer: this is an impossible task when done on a standard (planar) paper. (Want topical entertainment? Watch some youtubers solve this problem on a mug.) This is because $K_{3,3}$is non-planar, so by definition at least one of the lines has to cross!

$K_{3,3}$is a bipartite graph since it has two groups of 3 vertices; and within each group, none of the vertices are directly connected to one another.

K5 #

$K_5$is the complete graph of 5 vertices. (This means that each vertex is connected to every other vertex.)

We can see that $K_5$has 5 vertices and 10 edges. Since we know that all planar graphs have $E \le 3V - 6$, we can show that $K_5$certainly isn’t planar (since 10 is greater than 3(5)).

A striking fact: ALL non-planar graphs contain either $K_5$or $K_{3,3}$! This means that you can prove that a graph is either planar or nonplanar simply by showing that either of these component graphs can or cannot exist in a larger graph.

Graph Coloring #

A graph coloring assigns a color to each vertex such that every edge has two different colors on its two endpoints:

Often, we would like to figure out the minimum number of colors (categories) it takes to properly color a graph. This could have many uses, from register allocation to solving sudoku puzzles.

Six Color Theorem #

Let’s propose that every planar graph can be colored with 6 colors or less.

From Euler’s Formula, recall that $e \le 3v - 6$for any planar graph with more than 2 vertices. We also know that the degree of the graph is equal to $2e$.

So, the average degree of any given vertex is $\frac{2e}{v} \le \frac{2(3v-6)}{v} \le 6 - \frac{12}{v}$. This proves that there exists a vertex with degree at most 5 (due to the property of averages). Let’s try removing this vertex and see what happens.

Well, now each of the 5 neighbors each are assigned a different color. If we add the vertex back, then it can assume the 6th color. We can use this proof inductively to show that adding any vertex will result in the same thing occurring.

Five and Four Color Theorem #

It turns out that 6 is actually not the tightest bound we can put on the number of colors needed! It is possible to color all vertices with 5 colors or less and all faces with 4 colors or less in a planar graph. I won’t go into the details of these proofs here, but check out the bottom of Note 5 for the proof of the 5 color theorem, and Wikipedia has a good introduction to the (highly technical) 4 color theorem proof.